The Most Important Thing to Know Before You Start Wild Swimming

Cold Water Shock explained - what it is, why it’s dangerous, and how to stay safe

Cold Water Shock is your body’s immediate reaction when you first hit cold water. The sudden change in temperature triggers an automatic gasp for air, followed by fast, shallow breathing that can feel impossible to control. At the same time, your heart rate and blood pressure surge as your body diverts energy into survival mode. This reaction is completely natural, but it’s also the biggest cause of accidental drownings in the UK. Knowing what Cold Water Shock is — and recognising that it will pass if you stay calm and float — is the first step towards swimming safely and enjoying the water with confidence.

“Our guides come from mistakes we’ve made ourselves. Normally me.

The first time I experienced cold water shock was before we even started The Wild Swim Store. I’d signed up for my first triathlon and had just got my first OWS Wetsuit. Excited on a gorgeous April afternoon, I hurried straight into the sea.

Within seconds I couldn’t control my breathing - no matter how hard I tried.

I had to abandon the training session completely. That moment taught me just how real cold water shock is, and why understanding it matters.”

Enjoy the Cold

What is Cold Water Shock?

A simple routine to manage After Drop and feel great after wild swimming in the open water.

-

1. Enter slowly

Ease yourself in rather than jumping straight into the water.

-

2. Float first

Lie on your back and give your body time to adjust.

-

3. Control your breathing

Focus on steady, slow breaths until the gasp reflex passes.

-

4. Stay visible

Use a bright tow float & Swim Hat so others can see you if you get into trouble..

-

5. Swim short

Keep early swims brief until you build up experience.

DID YOU KNOW?

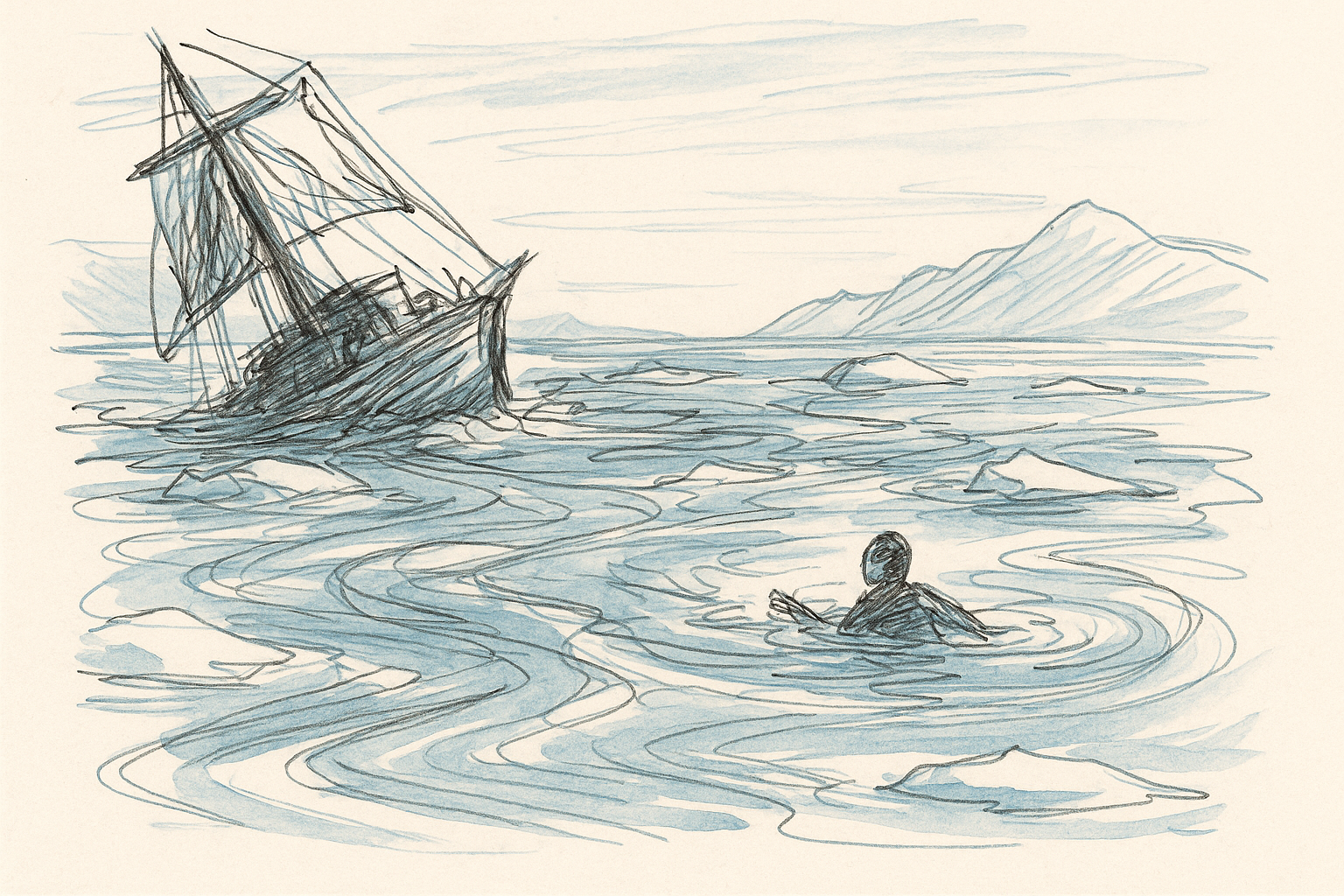

In 1984, an Icelandic fisherman named Guðlaugur Friðþórsson survived six hours in freezing ~5 °C sea water after his boat capsized near Heimaey Island. His survival, despite a core temperature plunging below 34 °C, is credited to his unusually thick layer of subcutaneous fat—often described as seal-like insulation that helped protect him from the cold and slow heat loss

The Science: What happens when you hit cold water?

Cold water shock is your body’s first, dramatic response to sudden immersion. When you step into chilly open water, your skin temperature plummets and nerves fire a warning. The immediate effect is an involuntary gasp, followed by rapid breathing. For some, it feels like the water is trying to steal your breath.

This spike in breathing rate, combined with a racing heart and a surge in blood pressure, makes the first 60–90 seconds the most dangerous. It’s the single biggest cause of drowning in UK waters — not because people can’t swim, but because the shock takes them by surprise.

Why it matters for wild swimmers

The science is simple: blood vessels in your skin tighten, driving blood towards your core to protect vital organs. That means your muscles stiffen and coordination drops just when you need control. Over time, with repeated swims, your body adapts, but everyone does so at a different pace.

The key takeaway

Cold water shock is temporary — usually gone in under two minutes — but you must respect it. If you know it’s coming, you can float, breathe, and give your body the time it needs to settle.

Cold Water Shock FAQs

How long does cold water shock last?

Usually between 60–120 seconds. The hardest part is the first gasp and burst of rapid breathing. Once you steady yourself and float, your body begins to adapt.

Can I train my body to handle cold water shock?

Yes — with gradual exposure, your body becomes less reactive over time. But adaptation varies: some adjust quickly, others take months. Never assume you’re immune.

Why does my chest feel tight in cold water?

The sudden temperature drop narrows your blood vessels and speeds up your breathing. This can create a feeling of chest pressure, but it eases once you calm your breath.

What’s the biggest risk with cold water shock?

The gasp reflex. If your head is under water when it hits, you can inhale water. That’s why entering slowly, staying visible, and floating on your back are key.

Do wetsuits or tow floats help with cold water shock?

A wetsuit slows the drop in skin temperature, reducing the shock. A tow float won’t reduce shock itself, but it keeps you visible and gives you support if you need to pause and float.